The Virginia Plan and the New Jersey Plan were two different plans for the structure of the United States government.

What are the differences between the Virginia Plan and the New Jersey Plan?

The Virginia Plan called for a bicameral legislature and a strong national government with three branches:

- Legislative Branch

- Executive Branch

- Judicial Branch

The New Jersey Plan called for a unicameral legislature and equal representation for each state.

Table of Contents

ToggleTable showing the differences between the New Jersey Plan and the Virginia Plan:

| Differences | Virginia Plan | New Jersey Plan |

|---|---|---|

| National Government | Strong National Government | Weaker National Government |

| Legislature | Bicameral Legislature | Unicameral Legislature |

| Representation | Representation by Population | Each State be Represented Equally |

| Power | More Power to Larger States | Disproportionate Power to Smaller States |

| Adoption | Formed Basis of New Constitution | Wasn’t adopted in original form |

The Constitutional Convention

In response to the Articles of Confederation’s inadequate government system, several states decided it was necessary to draft a new constitution granting the government more power.

It would also ensure the individual states and people retained many of their respective rights and liberties.

From May 25th to September 17th, 1787, delegates debated several aspects of the new constitution.

- The main talking points were:

- slavery

- the different branches of government

- what rights were protected and reserved for individual citizens (i.e., the Bill of Rights).

One of the more intensive debates centered around creating a bicameral legislature. If included, the constitution would establish both a Senate and a House of Representatives.

And while that wasn’t an issue, what was debated was how many votes each state would be allowed in terms of representation.

This is where the Virginia Plan and New Jersey Plan came into being.

Below, we’ll examine what the Virginia Plan offered, what the New Jersey Plan proposed, how they compared to one another, and what the ultimate decision the Founding Fathers took between the two was.

What Is the Virginia Plan?

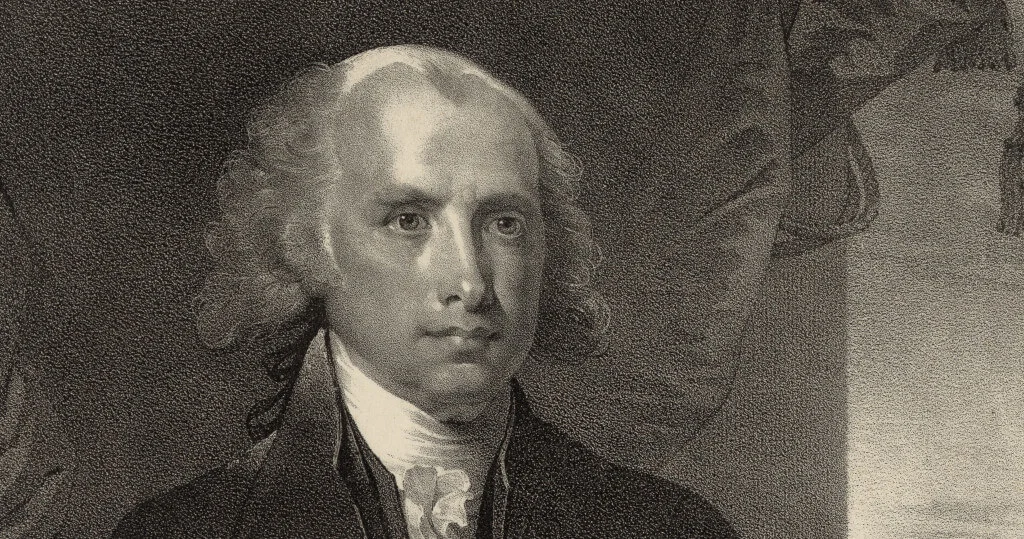

The Virginia Plan, also known as the “Large State Plan,” was first drafted by James Madison, a Virginian delegate.

The plan argued for three branches of government (the executive, legislative, and judicial), with the legislative branch comprising the Senate and the House of Representatives.

Creating the House of Representatives & the Senate

Unlike the election for members of the Confederation Congress who were elected by state legislature, the House of Representatives would be elected by that state’s population.

In contrast, House members would choose the Senate from a list of nominated candidates by their state’s legislature.

National legislatures would retain all of the existing powers of the Confederation Congress while also having the power to veto any state law deemed “incompetent.”

Creating the executive branch

The national legislature could decide on a national executive with the authority to execute all national and executive laws, including the power to start wars or create treaties.

The national executive could also work alongside several judges to create a “council of revision.” This council had the power to veto any state or national legislature. They could only be overridden if the respective legislature managed to get enough votes.

Creating the judicial branch

The Virginia Plan gave the judicial branch of government oversight and jurisdiction over felonies on the high seas (such as piracy) and jurisdiction over enemy captures.

Also, the impeachment of an official, cases that revolved around tax collections, and any case that dealt with citizens from multiple states or foreign countries.

The Virginia Plan also made state officials and officers take an oath to support the constitution. Any amendments to the constitution were possible without the assent of the national legislature.

The Virginia Plan’s most significant change

The most debated aspect of the Virginia Plan was about a state’s representation. It proposed that their part of the legislative Congress should be primarily based on the size of its population or its “quotas of contribution” (i.e., the amount of money raised via taxes to the federal government).

Regarding a state’s population, the sentiment only extended to non-slaves, meaning smaller states with a larger slave population would have less say than wealthier states or larger states with a smaller slave population.

Because of this radical departure from the Articles of Confederation, in terms of representation (each state got a single vote regardless of its size or wealth), it was given the title “The Large State Plan.“

Why the Virginia Plan deviated so much from the Articles of Confederation

The ultimate reason for the greater adoption of the Virginia Plan was that larger states carried a greater burden on them than the smaller states. This was both through innate size and the size of their contribution to the nation via taxes.

As such, it was argued that, along with the increased share of responsibility in relation to others, larger states should have a greater degree of representation.

Reaction in Congress

When the Virginia Plan was introduced, all its points were highly debated. When it came to its call for larger representation of Congress based on the size and wealth of the state, there was considerable dissent.

Larger states supported the plan, like Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania.

Meanwhile, many smaller states opposed it, arguing that every state should have equal representation regardless of size.

Because of this inclusion in the Virginia Plan, the New Jersey Plan was presented.

What Is the New Jersey Plan?

The New Jersey Plan, also aptly titled the “Small State Plan,” was presented by William Paterson and was created in response to the Virginia Plan.

The plan opted to retain much of the inherent structure from the Articles of Confederation, including its unicameral legislature and the one-vote per state status.

Get Smarter on US News, History, and the Constitution

Join the thousands of fellow patriots who rely on our 5-minute newsletter to stay informed on the key events and trends that shaped our nation's past and continue to shape its present.

It argued that giving too much power to the larger states created an unnecessary imbalance throughout the country. This would ultimately lead to larger states having greater power and sway over the union’s direction as a whole.

The New Jersey Plan’s propositions

The New Jersey Plan also included several other propositions that stood in stark contrast to the Virginia Plan.

These included:

- The amending of the Articles of Confederation rather than the installation of the constitution.

- Congress receiving additional powers to regulate commerce within the country and with other nations.

- Congress having the authority to raise funds through taxes, tariffs, and other methods.

- Establishing the Articles of Confederation as the law of the land, with the ability to enforce compliance among states if needed.

- A criminal can be convicted under the law of any state he commits the crime in, regardless of his state of origin.

Ultimately, the New Jersey Plan opted to fix many of the Articles of Confederation’s recognized issues while still attempting to maintain much of the state’s rights and state sovereignty originally granted.

How Do They Compare to One Another?

The Virginia Plan and the New Jersey Plan were almost complete opposites.

While the New Jersey Plan essentially sought to maintain much of the Articles of Confederation, the Virginia Plan wanted to replace it with a new constitution.

Because of this glaring discrepancy, both plans shared almost no similarities.

Legislative representation

Arguably their biggest point of contention was two very different views surrounding representation in Congress.

The Virginia Plan argued for two branches of the legislative Congress: the Senate and the House of Representatives. Under this new bicameral legislature, representation would be based on a state’s overall size or its “quotas of contribution” (i.e., the amount of taxes given).

In addition, House members would be elected by the people, while The House would choose senators from nominated state legislatures.

By contrast, the New Jersey Plan argued for the retention of the Articles of Confederation’s unicameral legislature and its “one vote per state” policy. Their position was that the states were independent entities that should remain as such upon joining the union.

As expected, this sentiment was shared mainly by many smaller states, including New York, Delaware, New Jersey, and (initially) Connecticut.

The branches of government

Their second largest difference was their respective views on dispersing power and checks and balances.

The Virginia Plan established both the executive and judicial branches and the existing legislative branch.

Under the executive branch, a “National Executive” would have the power to execute national laws, make war, or establish treaties with other nations.

The judicial branch would consist of a “Supreme Tribunal” (later known as the Supreme Court) that would hold jurisdiction over impeachments, felony crimes, or individuals that committed crimes in numerous states.

Like its stance on the legislative branch, the New Jersey Plan wanted to maintain the previous status under the Articles of Confederation, leaving much of the power in the hands of the states.

Congress would elect a federal executive that consisted of several people, all of whom could not be re-elected.

The plan also included a Supreme Tribunal, which would rule strictly over impeachment cases and the last stage of appeals when dealing with national matters.

Their ultimate objectives

Both plans were steeped mainly in their respective views surrounding the nation itself.

While initially presented to the Constitutional Convention as a way to remedy many of the weaknesses and deficiencies attributed to the Articles of Confederation, the Virginia Plan was determined at its very outset to completely reshape and restructure the government as a whole.

The New Jersey Plan was developed as a reaction to the Virginia Plan. It attempted to actively retain the Articles of Confederation while addressing its perceived flaws, such as its inability to enforce compliance among the states or establish interstate commerce.

Ultimately, their overall objectives were the biggest differences in comparing the Virginia Plan vs. the New Jersey Plan.

While state representation was their most glaring difference, it came down to the fact that the Virginia Plan had no intention of fixing the Articles of Confederation itself, whereas the New Jersey Plan did.

What Was Ultimately Decided?

Despite both plans having legitimate arguments for either side, on June 19th, 1787, the New Jersey Plan was rejected, with the majority voting for the Virginia Plan.

Because of this, many smaller states threatened to withdraw from the union. As Connecticut was the one state that sat divided between the two (particularly surrounding the representation given to all states), an agreement was established known as the Connecticut Compromise.

The Connecticut Compromise

Also known as “The Great Compromise of 1787”, the Connecticut Compromise was an agreement that was ultimately reached between the two parties.

In the compromise, the bicameral legislative structure was retained from the Virginia Plan. However, it established that the House would be chosen by popular vote, whereas the Senate would stay as a one-vote-per-state policy.

Unbeknownst to the smaller states and the proponents of the New Jersey Plan, this also included senators having longer terms than state legislators.

Consequently, senators would have much more freedom and independence than was initially considered by those against the Virginia Plan.

The End Result

Though much of the Virginia Plan was pushed through, that did not mean that some aspects of the New Jersey Plan did not make their presence known.

They ultimately forced a level of equal representation between the states in the Senate while also having many of its views regarding the judicial and executive branches be recognized.

A number of these sentiments were instrumental in forcing James Madison and others to draft the Bill of Rights, ensuring many of their ultimate fears regarding federal overreach would be significantly restricted.

At the same time, state and individual liberties would largely remain protected.