It’s often said that death and taxes are the only two certainties in life. But while taxes have been around for centuries, the present-day U.S Federal tax system came about much more recently and under some rather strange circumstances.

When Americans Didn’t Pay Income Tax

The British Crown had a slew of taxes the colonists expected to pay. Among them was a head tax, a set amount charged to every colonist, no matter their wealth. Property taxes were also imposed, as well as the infamous tea tax that incited the Sons of Liberty to take a stand and triggered the Boston Tea Party.

This pivotal moment in history marked the beginning of a new era in the colonies.

Following the colonies’ Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, the power to levy taxes was bestowed upon Congress as the representative body of the American people.

Some of the first taxes mandated by the newly-formed Congress included the oddly-named “Sin Taxes,” which were first imposed on alcohol and tobacco sales in 1794, and the estate tax in 1797 (which was used to fund the Navy).

As a curious side note, Great Britain established its income tax in 1799, after independence was secured on the other side of the Atlantic. It would eventually get repealed, only to be reintroduced soon after the Napoleonic wars.

Lincoln and the Prelude to the American Civil War (1860)

The American Civil War was arguably one of the most gruesome and traumatic events in United States history, with a death count reaching over 600,000. It also brought about numerous changes in the country’s economic and social landscapes.

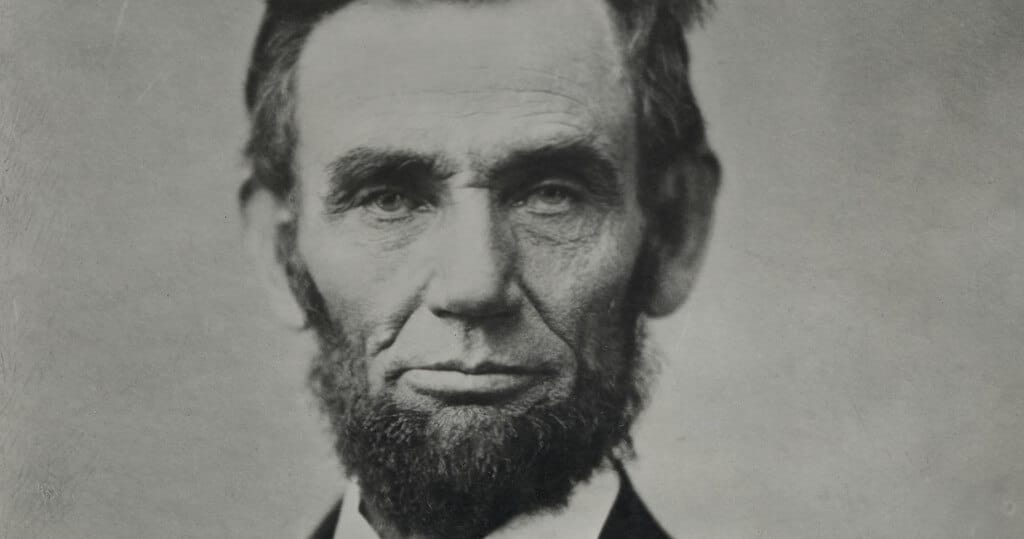

Then-president Abraham Lincoln took office in 1861 amid a decade-old dispute over the status of slavery.

Lincoln was an ardent opponent of the spread of slavery, as was evidenced by his disapproval of the Kansas-Nebraska Act that made those states into slave states. This position earned him the enmity of the Southern leaders.

The Start of the American Civil War (1861 – 1865)

What ensued was virtually unavoidable. When Abraham Lincoln emerged victorious in the 1860 presidential election, seven Southern states declared secession from the Union. In 1861, they formed the Confederacy, seizing federal government property and forts.

Within just one month of Lincoln’s rise to power, the Confederate army had marched towards Fort Sumter in South Carolina, an event that urged President Lincoln to take decisive military action.

Get Smarter on US News, History, and the Constitution

Join the thousands of fellow patriots who rely on our 5-minute newsletter to stay informed on the key events and trends that shaped our nation's past and continue to shape its present.

Amidst this increasingly hostile environment, Lincoln faced a very distressing predicament, as the tariffs that were currently in place could only suit a small federal budget, and the country was still recovering from the financial depression that ensued after the Panic of 1857.

There was simply not enough money to cope with the expenditures of a wartime economy. Furthermore, President Lincoln found opposition from within the Democratic Party and the anti-war circles of his own party, making matters a bit more challenging. Despite these adversities, some important advancements were made.

The Lead-Up to the First Income Tax

There was a pressing need to collect more money, especially when it became apparent that the war would not be resolved anytime soon.

In addition, the federal government feared that their ability to retrieve revenue from ports in the Southeast would be relinquished to the Confederacy, forcing them to take hurried measures.

Lincoln sent correspondence to Cabinet members Edward Bates, Salmon Chase, and Gideon Welles, asking for their opinion on the constitutionality of taxing revenue.

In a meeting held with Congress on July 4, 1861, the Cabinet, along with fellow Republican congresspeople, concluded that the income tax was an indirect tax and, therefore, not proscribed by Article I (Section 8, Clause 1) of the United States Constitution.

The Revenue Act of 1861

The first (and short-lived) federal income tax was enacted via the Revenue Act of 1861. It imposed a flat 3% tax rate on incomes above $800 (today’s equivalent of approximately $26,880).

This first act defined “income” in overly broad terms, encompassing any earnings derived from property, employment, professional trade, vocation, or “any source whatsoever.” It also taxed revenues generated both in the United States and abroad.

The 1861 Revenue Act was largely unsuccessful and failed to reach the desired milestone. This was because it could only be enforced on a minuscule percentage of the Northern population.

The Revenue Act 1862 – Progressive Income Tax and the IRS

The Revenue Act of 1862 called for the creation of the earliest version of the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), called the Office of the Commissioner of Internal Revenue.

The Internal Revenue Service body was in charge of collecting taxes from individual states during the war to afford sufficient military equipment, ammunition, and fully-trained troops.

This tax reform act also laid out the template for the current progressive income tax system by outlining different tiers for tax rates, doing away with the fixed rate in force at the time.

Thus, revenues in the tax bracket of $600 to $10,000 were taxed at 3%, while people with a turnover of $10,000 or more were charged a 5% income tax rate.

The 16th Amendment and the Constitutional Status of the American Income Tax

The first income tax (slightly modified by the Revenue Act of 1862) outlived the Civil War by almost seven years, being repealed in 1872 (barely eleven years after its enactment). However, the concept did not go away.

After a long hiatus and some failed attempts at reenacting an income tax, the 16th Amendment was approved and ratified by an overwhelming majority of state legislatures on February 25, 1913, though not without opposition.

For the most part, the northeastern states refused to accept this amendment – as the bulk of the wealth was heavily concentrated in those regions – but their efforts at resisting it were to no avail.

The Sixteenth Amendment was certified by Philander Knox, the Secretary of State at that time.