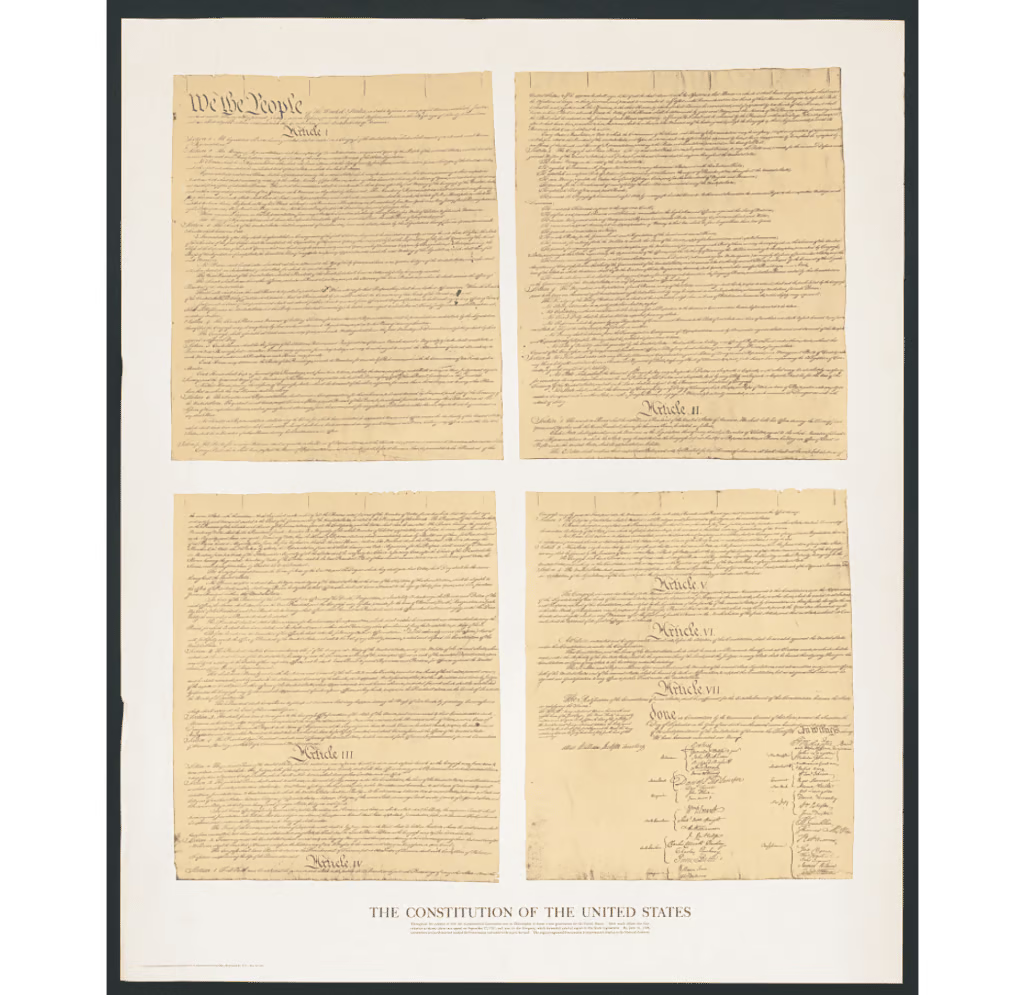

When administering justice, judges often have to analyze a wide array of “sources of law.” The United States legal system has various primary sources of law, such as the United States Constitution, state constitutions, case law, administrative law, and statutes.

Even though the United States is under the common law system (also called the Anglo-American law or case law), there are also written laws (often referred to as statutory laws), as we’ll see shortly.

Statute vs. Law

Statute law is a written form of public law or private law that is passed by a legislative body. It can be said that every statute is a law, but not every law is a statute.

In contrast, the term “law” generally refers to a set of rules that exist within a society and are enforced by governmental or administrative authorities. These rules may be written down, or they may be unwritten.

Get Smarter on US News, History, and the Constitution

Join the thousands of fellow patriots who rely on our 5-minute newsletter to stay informed on the key events and trends that shaped our nation's past and continue to shape its present.

In civil law countries, the law is virtually synonymous with the written law for practical purposes, even though they also occasionally recognize other unwritten sources of law.

What is the Difference Between Statutory (Civil) Law and Common Law?

Statutory Law

To speak of “statutory law” is to speak of the written law specifically. Civil law systems will endeavor to list and regulate the most relevant aspects of human relations in a code or series of codes.

Emperor Justinian I is known as the most influential figure in the development of the statutory law system through his compilation of the Corpus Juris Civilis in the 6th century.

This was essentially the codification of most of the imperial constitutions and Roman case law (jurisprudential) that were valid at that time.

A majority of countries worldwide operate within the framework of the statutory law system, including Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking countries in Central and South America, as well as most European countries.

Common Law

In common law systems, the written law is not as prominent, with judicial precedents and past judicial opinions being the main drive behind a judge’s decision.

Common law, in this context, is the law that has been passed down through judicial decisions.

There are also elements of common law in civil or statutory law systems. For example, most civil law courts have to abide by the binding interpretations set out by their superior court.

The common law system (based on English and American law) is also practiced in countries such as Australia, New Zealand, Fiji, Jamaica, Bangladesh, India, Liberia, and many others.

United States Statutory Law

Statutory laws in the United States are passed by either a state’s legislature or the United States Congress.

The laws in question can be Public Law or Private Law. Public Law generally concerns the public and comprises the bulk of the U.S. legislative corpus.

Private Law targets institutions and specific persons.

A statutory law becomes public once Congress passes a bill and the President signs it. Such a public law is first released as a slip law that is then added to the Statutes at Large.

They are then categorized, indexed, and published in the United States Code.

Legislative Process

For simplicity’s sake, the process that’ll be described below is for federal statute law.

The legislative process begins with the introduction of the proposed bill to a chamber of the United States Congress by a representative.

This bill project is assigned to a committee for assessment. Once released, it’s placed on the calendar to be debated, voted on, or amended if needed.

Once the bill passes by a simple majority, it’s sent to the Senate, which, in turn, assigns it to another committee for further study. Upon being released, it’s likewise debated and voted on.

Suppose 51 out of 100 senators (simple majority) approve this bill.

In that case, it is then compared against the House of Representatives’ version of the bill by a joint conference committee composed of both House and Senate members.

The final draft that results from the conference committee’s debates is sent back to the House and Senate for final approval, after which the Government Printing Office “enrolls” the bill (prints it on parchment.)

The President can either sign or veto the enrolled bill within the next ten days. If Congress is adjourned during the ten day period the President has to review legislation and he decides not to sign, then a pocket veto occurs.

The United States Code

The United States Code (also named “U.S. Code”) is a chief example of United States statutory law.

It’s a consolidation of general and permanent federal statutes comprised of 54 titles, each dealing with subjects such as:

- Defense

- National Guard

- Internal Revenue

- Public Health

- Copyrights

- Patents

- Law Enforcement

- Postal Service

Apart from the 54 titles just mentioned, there is a section called “Popular Names and Tables.” This lists revised titles, statutes, and executive orders.

The contents of this code appear in the United States Statutes at Large, which records all Acts of Congress and concurrent resolutions passed by the federal legislature.

However, browsing the entire Statutes at Large is inconvenient for jurists and legal professionals since they’d have to sift through a chronological list of acts.

The United States Code attempts to compact all relevant federal statutory laws into one volume for consultation.

Interpretation of Statutory Law

Judges are bound to apply statutory law in a strict sense or by following the rules of interpretation set in the specific code it’s contained in.

The judge recognizes that the ultimate legislative power resides in Congress under Article I, Section 1 of the United States Constitution.

There are various methods for interpreting a statutory provision. Additionally, other aspects have to be factored into the interpretation, such as the broader statutory context and what the “legislator” aimed to achieve with the law, as well as the purpose of the law itself.