Table of Contents

ToggleIsolationism Under Attack

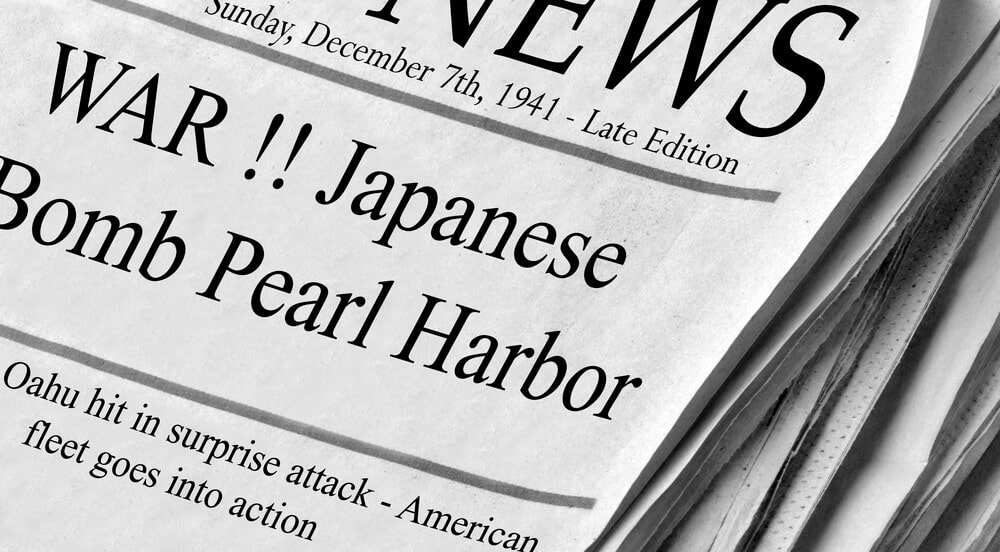

The United States ended its isolationist policy and entered the Second World War as an active combatant following the December 7th attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941.

Until this point, a great debate had been raging in the American political sphere about whether the United States should end its neutral stance.

The experience of World War I and the Great Depression of the 1920s had contributed to an environment for the isolationist policy that held sway throughout the 1930s.

While the attack on Pearl Harbor was certainly the catalyst for the country’s change in policy, the country had been inching toward war for years.

Many citizens argued that World War II was a European war and should remain as such. Still, they faced growing calls for American intervention on moral and political grounds.

In the end, some argue that America’s hand was forced by Japan, but this is only partly true.

Why did the United States enter WW2?

There is no single answer to why the United States entered the fray when it did. Instead, there were four main reasons why the nation ultimately chose to enter WW2 as an active combatant, as well as a multitude of contributing reasons which came together to spur a sleeping giant into action.

Four Key Reasons Why the United States Entered World War II

Public opinion inside the United States began to shift in favor of aiding the Allies to win the fight in Europe long before the attack on Pearl Harbor and the mobilization of the United States military.

The following factors were highly influential in shifting the ‘great debate’ in the United States in favor of interventionist policies.

Concern about continued German expansion and imperialism

While his countrymen were divided, President Franklin Roosevelt believed intervention would be necessary.

In 1939, President Roosevelt convinced Congress to allow for the sale of war materials to allies like Great Britain and France on a cash-and-carry basis.

In 1940, the President expressed his belief that the idea that an isolationist policy would protect the United States was “delusional” at a commencement address at the University of Virginia.

He also indicated that he felt Nazi Germany’s expansion would continue until it reached American soil if not forcibly halted.

Continued German expansion seemed to remain a concern for Roosevelt (as well as a larger percentage of the nation’s populace) in mid-1941, too, because he met the Prime Minister of Great Britain, Winston Churchill, to establish the Atlantic Charter and openly called for an end to “Nazi tyranny” before the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

German aggression and unrestricted use of submarine warfare

While isolationists believed that the war in Europe was a primarily European concern, this view began to change rapidly in the face of unrestricted German aggression at sea.

German war policy changed as United States war materials began to reach the allies. As they had during World War I, the Germans lifted restrictions on submarine warfare.

This move was not unexpected, but it did influence the popular mentality within the country as it put merchant vessels from the United States in danger. As non-military ships from the United States began to come under fire, calls for America to enter the war intensified.

Many argue that lifting restrictions on submarine warfare, combined with remaining tensions from World War One, made the United States’ intervention in World War Two inevitable.

Japanese imperialism and the control of China

Just as the United States had suffered during the Great Depression, Japan experienced its own financial crisis. In 1931, sensing an opportunity to seize land rich in raw materials and increase its ability to grow economically, Japan invaded Manchuria.

The United States, at this time, had amicable relations with both China and the USSR (despite suspicion and unease at the recent communist takeover). As a result, they joined the USSR and China in strongly condemning this action.

The resulting back and forth led to Japan leaving the League of Nations and contributed to growing tensions between the countries.

When Imperial Japan entered a Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy in 1940, concerns in the United States and amongst Great Britain and her allies regarding Japanese imperialism and aggression grew.

Furthermore, this addition to the Nazi Germany support base left many in the United States more certain than ever that intervention would be necessary.

The Bombing of Pearl Harbor

The increasing levels of Japanese aggression and multiple seizures of territories within their reach had already prompted strong calls for action in the United States.

Concerns mounted as Japanese territories crept closer to the United States-controlled areas of the Pacific. Many, including President Roosevelt, felt that American entry into their own theater of war was only a matter of time.

The attack on Pearl Harbor was a seismic event. Initially intended to be a weakening blow to the United States so that Japanese forces could move on the Dutch East Indies and British Malaya, it backfired spectacularly.

Get Smarter on US News, History, and the Constitution

Join the thousands of fellow patriots who rely on our 5-minute newsletter to stay informed on the key events and trends that shaped our nation's past and continue to shape its present.

While the goal was to weaken the United States Navy and perhaps discourage further American aid to the Allies, it caused outrage.

The Japanese Empire did succeed in its short-term goal of crippling United States forces in the Pacific. This meant that they could seize primary control of Guam, the Philippines, and British Malaya.

However, the morning after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States officially declared war on Japan.

Support For Intervention Slow To Reach Critical Mass

While these external factors undoubtedly formed the main reasons for the eventual entry of the United States into the Second World War, the political stance of interventionism had been present throughout the war.

The reluctance to engage in the war effort in Europe was spurred by isolationist ideals carried forward from World War I.

President Woodrow Wilson’s optimistic belief that American involvement in World War One would lead to a lasting peace being proven wrong was one reason that the United States initially rejected intervention.

By the late 1930s, roughly only 10% of Americans believed that United States intervention was needed or desired.

Pearl Harbor, the Catalyst

By 1940, bodies such as the Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies (CDAAA) were lobbying for action. This CDAAA alone had 75 local chapters across the country and roughly 750,000 members.

The bombing of Pearl Harbor and active violence against United States citizens by Imperial Japan and Adolf Hitler’s Germany can be cited as providing the impetus needed for declaring war.

Nonetheless, the political landscape that moved the United States from isolationist to interventionist policies was complex and varied.