Table of Contents

Toggle

Click here to see Article 5 of the US Constitution.

Article V is just one section, with approximately 143 words. It’s shorter than what you are reading now. On a phone screen, the whole text fits in a single scroll. It uses the word “shall” five times.

Get Smarter on US News, History, and the Constitution

Join the thousands of fellow patriots who rely on our 5-minute newsletter to stay informed on the key events and trends that shaped our nation's past and continue to shape its present.

Summary of Article 5

The United States Constitution is famously difficult to change.

Article V of the U.S Constitution describes the formal process for amendments, balancing stability with the ability to adapt over time.

This article examines Article V in detail, exploring why the Framers designed the amendment process as they did, how the Constitution has actually been amended over time, and the challenges of passing amendments in the modern era. It also analyzes differing perspectives on constitutional change – from the debates of Federalists and Anti-Federalists in the 1780s to modern arguments between originalists and living constitutionalists.

Finally, it evaluates the prospects of seeing another constitutional convention or major amendment in the foreseeable future, given historical precedent and today’s political dynamics.

Key Facts About Article V:

-

Allows amendments by Congress or state convention.

-

Requires two-thirds of Congress or states to propose.

-

Needs three-fourths of states to ratify.

-

Only 27 amendments in U.S. history.

Article V Amendment Process – How Amendments Are Proposed and Ratified

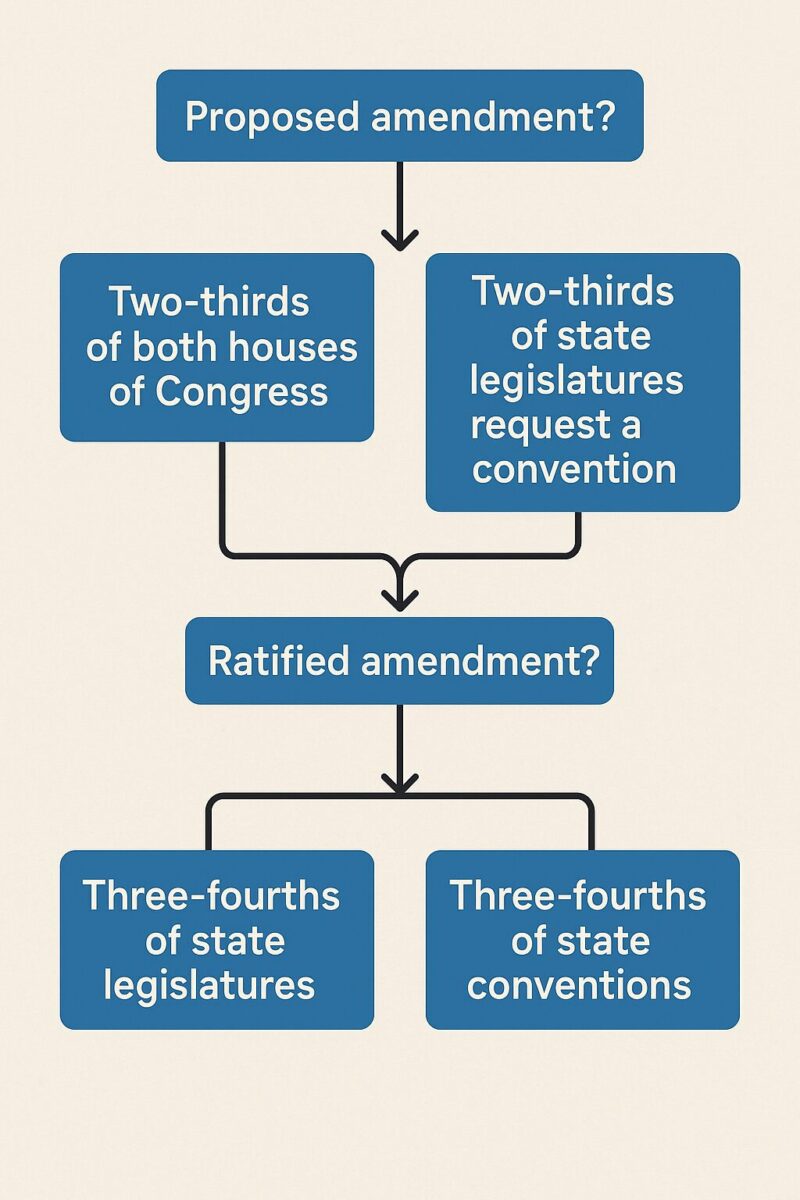

Article V of the U.S. Constitution provides two methods to propose amendments and two methods to ratify them.

Under Article V, an amendment can be proposed in two ways:

- By Congress, with a two-thirds vote in both the House and Senate.

- By a national convention called by Congress when two-thirds of state legislatures apply.

Ratification also has two options:

-

Approval by three-fourths of state legislatures (38 states).

-

Approval by conventions in three-fourths of the states.

Congress gets to choose which ratification method will be used for each amendment.

Importantly, Article V sets one permanent limitation: no state can be deprived of its equal representation in the Senate without that state’s consent. In addition, Article V originally prohibited any amendment before 1808 that would affect the slave trade or direct taxation provisions, a clause that became obsolete after 1808.

Another important feature is that the President has no role in the Article V process, either in proposing or ratifying amendments.

Congress may also set a ratification deadline in the proposing resolution, often seven years, but the Constitution itself does not require one.

Why the Framers Made the Amendment Process Difficult:

The Framers designed Article V to balance flexibility with stability. James Madison said it “guards equally against that extreme facility… and that extreme difficulty” in changing the Constitution, ensuring amendments happen only when there is a broad national consensus.

Two Ways to Propose Amendments: Congress and State Conventions

Article V allows amendments to be proposed either by Congress or by a national convention called when two-thirds of state legislatures apply. This convention option, added at George Mason’s urging, was meant as a “constitutional safety valve” in case “no amendments of the proper kind would ever be obtained by the people, if the Government should become oppressive.” It has never been used, but its existence has at times influenced Congress to act.

| Proposal Method | Who Initiates | Ratification Method | Historical Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| By Congress | U.S. House and Senate with two-thirds vote in both chambers | By State Legislatures – Three-fourths of states (38 of 50) must approve | Used for most amendments (e.g., Bill of Rights, 14th Amendment) |

| By Congress | U.S. House and Senate with two-thirds vote in both chambers | By State Conventions – Three-fourths of states (38 of 50) must approve | Used only once – 21st Amendment repealing Prohibition |

| By State Convention | Called by Congress when two-thirds of state legislatures (34 of 50) apply | By State Legislatures – Three-fourths of states (38 of 50) must approve | Never used |

| By State Convention | Called by Congress when two-thirds of state legislatures (34 of 50) apply | By State Conventions – Three-fourths of states (38 of 50) must approve | Never used |

Origins and Purpose of Article V in the U.S. Constitution

Learning from History:

Learning from the rigid Articles of Confederation, which required unanimous consent for changes, the Framers created an amendment process that allowed important revisions without unanimity, while still demanding supermajority approval.

Framers’ Intent:

The delegates’ goal was to ensure the Constitution could evolve, but only with substantial agreement. They believed some provisions would need revision or addition over the years, but they wanted changes to reflect a broad consensus of the American people.

James Madison noted that it was “requisite… that a mode for introducing [useful alterations] should be provided.”

The solution they crafted allowed both Congress and the states to propose corrections or additions to the constitutional framework.

Alexander Hamilton, in Federalist No. 85, argued that it would be easier for the united people of the new republic to adopt amendments later than to try to rewrite the Constitution upfront during ratification. He pointed out that once the Constitution was in place, any needed amendment would be just “a single proposition” requiring agreement of three-fourths of the states, rather than having to start from scratch with all states unanimous.

Hamilton assured skeptics that whenever an amendment was truly necessary, enough states would rally behind it so that it “must infallibly take place.”

Federalist vs. Anti-Federalist Views:

Federalists saw Article V as a safeguard against flaws in the Constitution, while Anti-Federalists feared the bar was too high. Their push for explicit protections led directly to the Bill of Rights in 1791.

Historical Evolution Through Amendments

Since 1789, the Constitution has been amended 27 times, often in response to major national events such as the Civil War, the Progressive Era, and the civil rights movement. See our Complete Guide to Constitutional Amendments for details on each.

Progressive Era Amendments (1913–1920)

The early 20th century saw a flurry of amendments driven by Progressive Era reform movements aiming to make government more responsive and society more just. Four amendments in the 1910s addressed long-debated issues:

- 16th Amendment (ratified 1913): Authorized Congress to levy an income tax without apportioning it among the states by population. This came after a Populist and Progressive campaign to tax higher incomes; it effectively overturned an 1895 Supreme Court ruling (Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan & Trust Co.) that had struck down a previous federal income tax law. The amendment was born of growing concern about inequality and the need for the federal government to have a stable revenue source beyond tariffs. It showed how a combination of public opinion (many Americans supported taxing the wealthy) and practical fiscal need led to constitutional change.

- 17th Amendment (ratified 1913): Established the direct election of U.S. Senators by the people, instead of senators being chosen by state legislatures. This reform was pushed by Progressives who argued that the Senate had become a “millionaires’ club” rife with corruption and backroom deals in state legislatures. Over several decades, public pressure mounted as reformers and many state governments themselves advocated for direct elections. By the early 1900s, the call for this change was so widespread that Congress finally proposed the amendment. It’s an example of a political movement (for greater democracy and accountability) forcing a structural change in the Constitution.

- 18th Amendment (ratified 1919): Instituted national Prohibition of alcoholic beverages. The drive for Prohibition was led by the temperance movement – a coalition of social reformers, many churches, and women’s groups – which had been growing since the 19th century. By the 1910s, World War I added momentum (with arguments that grain should be used for food, not liquor, and linking alcohol to unpatriotic behavior). The 18th Amendment shows how a passionate social movement can succeed in amending the Constitution, albeit temporarily. (This amendment would later be the only one ever repealed.)

- 19th Amendment (ratified 1920): Granted women the right to vote. This was the culmination of the women’s suffrage movement that had begun in the mid-1800s with leaders like Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and many others. After decades of advocacy, protests, and state-level victories (some states had already given women voting rights), a broad national consensus finally emerged that denying half the population the vote was unjust. The drive gained crucial support after World War I, as women’s contributions to the war effort underscored their claim to equal citizenship. The 19th Amendment stands as a landmark expansion of democracy, achieved through persistent social activism and changing public attitudes.

Mid-20th Century Changes (1933–1967)

Amendments slowed during the mid-20th century but still addressed important governance issues arising from historical circumstances:

- 20th Amendment (ratified 1933): Shortened the “lame-duck” period by moving the start of new Congressional terms to January 3 and the presidential inauguration to January 20 (from March, as originally set). This reform came during the Great Depression. After Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected in November 1932, the country had to wait four months (until March 1933) for him to take office while the economy crumbled. Public consensus grew that the transition period was too long. The 20th Amendment was a practical fix to make government more responsive and reduce the awkward gap when outgoing officials were inactive or unaccountable lame ducks.

- 21st Amendment (ratified 1933): Repealed the 18th Amendment, ending Prohibition. By the early 1930s, it was clear that Prohibition had failed – it had led to organized crime, speakeasies, and general public disregard for the law, and it deprived governments of tax revenue during the Depression. The call to repeal crossed party and regional lines, uniting a large majority of Americans. The 21st Amendment is notable not only as the sole repeal of another amendment, but also for its ratification process – it was ratified by state conventions rather than state legislatures, the only time that method has been used. This choice was made to speed up ratification and because many state legislators were still elected on “dry” tickets and might not reflect public opinion. The swift repeal of Prohibition underscored that even after an amendment is adopted, public sentiment can reverse dramatically, necessitating another amendment.

- 22nd Amendment (ratified 1951): Limited the President to two terms in office (or a maximum of ten years if finishing part of a predecessor’s term). This amendment followed Franklin D. Roosevelt’s unprecedented four elections to the presidency (1932, 1936, 1940, 1944). After FDR’s long tenure, and once a new Congress dominated by the opposition party (Republicans) came in 1947, there was strong support for formalizing the two-term tradition that George Washington had started. The 22nd Amendment reflected a belief, shared by many across the political spectrum, that no one person should hold too much power for too long, and it showed how a singular historical experience (FDR’s presidency) produced a lasting constitutional change.

- 23rd Amendment (ratified 1961): Gave the District of Columbia the right to participate in presidential elections by allocating it electoral votes (up to the number of the smallest state, which is 3). Washington, D.C., had long been unique: its residents could not vote for President and had no voting representatives in Congress, despite living in the nation’s capital. By 1960, the population of D.C. was large and the denial of a presidential vote was seen as a glaring democratic gap. The 23rd Amendment was a modest step to include D.C. in the electoral college (though D.C. still has no voting Congress members). Its passage during the Cold War era also had symbolic value, as the U.S. sought to demonstrate its commitment to democracy – allowing citizens of the capital city to vote for the nation’s leader was seen as the right thing to do.

- 24th Amendment (ratified 1964): Banned poll taxes in federal elections. Poll taxes had been used in many Southern states as a means to disenfranchise poor African American (and white) voters, since paying a fee was required to vote. By the 1960s, the civil rights movement was in full swing, and there was broad recognition that poll taxes were an unjust barrier to voting. The 24th Amendment outlawed this practice for federal elections (and later, the Supreme Court would extend this principle to state elections as well). This amendment was part of the broader civil rights era push to make the promises of the 15th Amendment (voting rights) a reality.

- 25th Amendment (ratified 1967): Addressed presidential succession and disability. This amendment came on the heels of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963. It clarified the process for filling a vacancy in the vice presidency (previously, there was no way to replace a Vice President until the next election) and established procedures for the Vice President to serve as Acting President if the President becomes unable to perform duties (for instance, due to surgery or illness). The 25th Amendment had wide bipartisan support as a good-government measure to ensure continuity and stability in the executive branch during emergencies. It has been invoked several times for temporary transfers of power during medical procedures, and Section 2 was used to fill vice-presidential vacancies in the 1970s. This amendment shows how a crisis (the JFK assassination and the Cold War context) focused attention on constitutional gaps that needed to be fixed for the functioning of government.

The Vietnam Era and Modern Amendments (1971–1992)

The most recent amendments reflect the pressures of the Vietnam War era and unique historical anomalies:

- 26th Amendment (ratified 1971): Lowered the voting age from 21 to 18 for all elections. The slogan “old enough to fight, old enough to vote” encapsulated the driving force behind this change – during the Vietnam War, young Americans were subject to military draft at 18 but in many states could not vote until 21. There was a strong youth movement and broad public agreement that this discrepancy was unfair. In 1970, Congress tried to mandate a lower voting age by statute, but the Supreme Court (in Oregon v. Mitchell) ruled that Congress could only lower the voting age for federal, not state, elections. This situation virtually required a constitutional amendment to create a uniform rule. The 26th Amendment was passed by Congress and ratified by the states with remarkable speed (it became the fastest-ratified amendment in U.S. history) – demonstrating that when an issue has overwhelming consensus, the Article V process can still move quickly.

- 27th Amendment (ratified 1992): This amendment bars any law that changes the compensation of members of Congress from taking effect until after the next House election. The story of the 27th Amendment is unusual: it was originally proposed in 1789 as part of James Madison’s package of amendments (what became the Bill of Rights) but was not ratified by enough states at that time. It lingered dormant for nearly 203 years until the 1980s, when a university student’s research project reignited interest in it. Ultimately, more states ratified it, and in 1992 it crossed the required threshold to become part of the Constitution. The 27th Amendment’s content was not controversial in modern times – it essentially prevents Congress from giving itself an immediate pay raise – but the amendment’s extremely delayed ratification raised interesting legal questions. (Congress eventually recognized it as valid, given that Article V does not impose an explicit time limit unless Congress sets one.) While not indicative of the typical amendment process, the 27th Amendment underscores that amendments can still happen under unusual circumstances, and that an idea from the Founding era can become law in the 20th century if the conditions allow.

- Failed Amendments and Modern Attempts: Since 1992, no new amendment has been added, marking one of the longest stretches in U.S. history without a constitutional change. Several high-profile amendment efforts have failed in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. The most noteworthy was the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which aimed to guarantee equality of rights regardless of sex. Congress approved the ERA and sent it to the states in 1972 with a seven-year ratification deadline. Initially, it gained rapid support and 35 of the needed 38 states ratified it. However, a conservative backlash led by activists like Phyllis Schlafly mobilized opposition, and no additional states ratified before the deadline (Congress extended the deadline to 1982, but it still fell short). In recent years, a few more states symbolically ratified the ERA long after the deadline, sparking debate about whether it could still be adopted, but as of now it remains unratified and its future is legally uncertain. Other attempts have included the District of Columbia Voting Rights Amendment (proposed in 1978 to give D.C. full representation in Congress, it expired in 1985 far short of ratification), various versions of a balanced budget amendment (a perennial proposal, sometimes passing one house of Congress but never fully adopted), amendments to ban flag burning or prohibit same-sex marriage, and more. These failures highlight how difficult it has become to achieve the broad consensus needed for amendment, especially on divisive social or political issues.

As George Washington said in his Farewell Address, “The basis of our political systems is the right of the people to make and to alter their Constitutions of Government. But the Constitution, which at any time exists, till changed by an explicit and authentic act of the whole People, is sacredly obligatory upon all.” This balance between the right to change and the need for stability is exactly what Article V was designed to protect.

Prospects for a Future Convention or Major Amendment

While an Article V convention is possible in theory, none has ever been held. The closest efforts have come from state campaigns for a balanced budget amendment, which remain a few states short of the 34-state requirement. In Congress, the two-thirds vote threshold and partisan divides make major amendments unlikely unless a unifying national issue emerges.

The amendment process, as Article V envisions, remains a crucial part of the constitutional system, even if it is infrequently used: it is the mechanism by which the American people, at the highest level, can alter their fundamental law, and its existence can influence political behavior (as seen by the pressure campaigns for amendments). Whether America will experience another burst of amendment activity or a convention is uncertain, but understanding Article V’s history and challenges helps explain why such changes are so rare and significant when they do occur.