Table of Contents

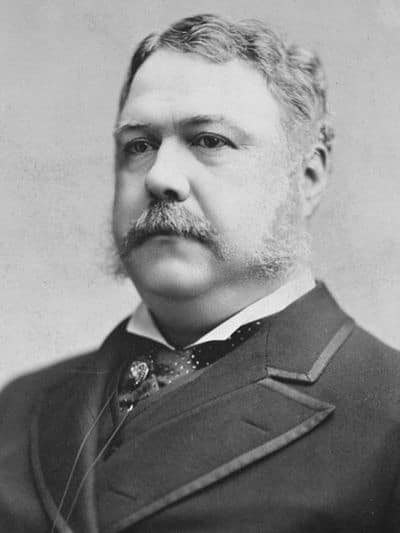

ToggleWhen was Chester A. Arthur born?

Chester A. Arthur was born in 1829.

Where was Chester A. Arthur born?

Chester A. Arthur was born in Fairfield, Vermont.

How old was Chester A. Arthur when he became president?

Chester A. Arthur was elected at the age of 51.

What years was Chester A. Arthur president?

Chester A. Arthur was president from 1881 – 1885.

When did Chester A. Arthur die?

Chester A. Arthur died at the age of 57 in 1886.

How did Chester A. Arthur die?

He died of a stroke.

Early Years

Chester Alan Arthur was born in Fairfield, VT on October 5, 1829, the fifth of nine children to William and Malvina Stone Arthur.

Because Chester’s father was a pastor in the Free Will Baptist Church, his family moved several times during his youth. Chester grew up in several towns in upstate New York.

Chester attended the Lyceum of Union Village (a grammar school) for his college preparation and attended Union College in Schenectady, NY at the age of 16. During his winter breaks, Chester often taught school in the town of Schaghticoke and after graduating from college in 1848, he moved to Schaghticoke to teach full time.

Arthur’s Young Adult Years

While he was a teacher, Arthur started studying law. He taught for a time in North Pownal, VT, and was a principal at a school in Cohoes, NY. After completing his studies at the State and National Law School in 1853, Arthur moved to New York City to read law at the law office of Erastus Culver. When he was admitted to the bar the next year, Arthur joined Culver’s law firm, which was renamed Culver, Parker, and Arthur.

During his time practicing law, Arthur was involved in cases that advocated for abolition. One such civil rights case led to the desegregation of the New York City streetcar lines.

In 1856, Arthur began a new partnership with a friend and moved to Kansas to practice law. Though he was a proponent of the anti-slavery faction in the territory, he and his friend did not enjoy the frontier lifestyle of the region and moved back to New York after only a few months.

Upon his return, Arthur began courting Ellen Herndon, whom he married in 1859. Together, the couple had three children.

Arthur’s Rise In Politics

In the succeeding years, Arthur built a successful law practice of his own to support his family. Arthur also became involved in politics and rose in prominence in the new Republican Party.

Arthur was also busy in the role of Judge Advocate General for the 2nd Brigade, New York Militia. With the outbreak of the Civil War, Arthur was promoted to the rank of brigadier general and appointed to the quartermaster department of the New York State militia.

His skills as an organizer gained him the promotion in March 1862 to the position of the state militia Inspector General and later that year he was promoted again to be Quartermaster General.

Despite the quality of his performance, Arthur was relieved from his position after New York elected a Democratic governor. The position he held was a political appointment and the new governor appointed a Democrat to fill the post.

After losing his position in the army, Arthur resumed his work as a lawyer. This turned out to be a prosperous change. With the contacts he had made in the military, his law firm prospered.

Arthur also became more active in Republican politics. Arthur used the important contacts he had made when he was with the New York militia and through his law practice to rise in prominence in the New York Republican Party.

Get Smarter on US News, History, and the Constitution

Join the thousands of fellow patriots who rely on our 5-minute newsletter to stay informed on the key events and trends that shaped our nation's past and continue to shape its present.

In 1868, Arthur became the chairman of the New York City Republican executive committee. By the end of the decade, Arthur shifted more of his energy toward politics. Arthur served for two years as counsel to the New York City Tax Commission and then was appointed by President Grant as the Collector of the Port of New York.

This was a lucrative position both from his salary and more from the extra money he earned from what was known as the moiety system. This system awarded the collector a percentage of levies and fines, and the cargoes seized for illegal activity.

Because of the large income from his position, the Arthurs enjoyed a lavish and wealthy lifestyle. The position also gained Arthur more notoriety because he was popular with his subordinates.

But it was not to last.

Many criticized the moiety system as corrupt as the patronage system that used the collector’s post to collect money for the political party and appoint party members to key positions.

After Rutherford B. Hayes replaced President Grant in 1877, Arthur lost his job (and large salary) in 1878 from sweeping reforms of patronage practices and the elimination of the moiety system.

Even after his term ended, Arthur remained popular in New York politics. With time on his hands, Arthur devoted his energy to campaigning for Republican candidates for New York elections.

It was while he was away from home attending to campaign matters that he learned of the sudden death of his wife on January 12, 1880. This was a devastating blow for Arthur and he never remarried.

Arthur As Vice President

Later that year the Republican Party Convention nominated James A. Garfield as their candidate for President. Garfield chose Arthur as his running mate as a strong eastern candidate and to help gain the critical New York electoral votes. The election was a close call, winning by only 7,018 popular votes. The Republican victory was in large part due to Arthur’s campaigning efforts.

With the Republican victory, Garfield and Arthur became the 20th President and Vice President of the United States respectively.

As Vice President, Arthur presided over an evenly divided Senate, with thirty-seven Republicans and thirty-seven Democrats. Arthur often was the tie-breaking vote to issues favorable to Republican Party interests.

The Senate often was deadlocked over many of President Garfield’s nominations to the various government positions.

Making things complicated was the infighting within the Republican Party with factions opposed to the faction that President Garfield supported.

At the close of the congressional session, Arthur left Washington D.C. and returned to New York to attend to state political matters.

Arthur’s vice presidency lasted less than seven months. On July 2, President Garfield was shot by a deranged office-seeker and died eleven weeks later on September 19.

A curious problem arose during the two and a half months that President Garfield lingered on from his wounds. The President was still alive but unable to handle his duties. Arthur was reluctant to assume the responsibilities of President so long as Garfield was alive.

Additionally, the U.S. Senate was in adjournment and had not appointed anyone to the position of president pro tempore after the person in that position had resigned. With no legal guidance for presidential succession (the 25th Amendment settled this issue eighty-six years later), there was a power vacuum over the summer of 1881.

The issue was settled with Garfield’s death on September 19. Arthur, who had remained in New York, was sworn in as the 21st President of the United States at 2:25 AM on September 20 by New York Supreme Court Judge John R. Brady.

Arthur As President

After traveling to Washington later that day, President Arthur took steps to call the Senate to appoint a president pro tempore.

He retook the oath of office on the 22nd officiated by Chief Justice Morrison R. Waite to clear up any question of whether a state court judge had the authority to administer the presidential oath of office.

Arthur took up residence initially at the home of Senator John P. Jones while an extensive White House remodeling that he ordered took place.

By this time, Arthur’s son was a student at Princeton University and his daughter remained in New York under the care of a governess until the work on the White House was completed. Arthur’s sister, Mary Arthur McElroy served as his White House hostess, as he remained a widowed bachelor throughout his presidency.

Arthur faced numerous challenges upon taking Garfield’s place. Many speculated that he was corrupted from his involvement in New York City politics. Almost right away, Arthur clashed with Garfield’s cabinet because Garfield and his cabinet were part of the Republican Party faction in opposition to the faction Arthur belonged to. Despite this, Arthur requested that they remain in their positions at least until Congress reconvened.

Within the year all of the cabinet members resigned, with the lone exception of Secretary of War Robert Todd Lincoln.

Despite once being a beneficiary of the spoils system in politics, Arthur surprised many by carrying out reforms to civil service agencies. He put a stop to fraud within the postal system. He supported congressional civil service reform legislation and signed the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act on January 16, 1883.

Not stopping there, Arthur quickly appointed proponents of reform to the Civil Service Commission (which the law created) to appoint civil servants based on their merits rather than their political connections. Arthur also advocated the reform of the complex tariff structure that was in place at the time and created a tariff commission.

Another area of reform that Arthur addressed was the U.S. Navy. After the Civil War, the state of the navy declined with the military emphasis on the wars in the West against Native American tribes. At Arthur’s urging, Congress apportioned funds for the construction of eight modern ships to the U.S. naval fleet.

Arthur attempted reforms in civil rights issues in the South, but with limited success. Rather than supporting the weak Southern Republican Party in the South, his administration supported independent parties as more liberal and in their policies toward African Americans.

Arthur was disappointed with the Supreme Court struck down the Civil Rights Act of 1875 while considering several civil rights cases. He also was unsuccessful in persuading Congress in passing any new civil rights legislation.

Arthur was able to intervene on behalf of a Black West Point cadet to overturn a court marshal ruling that was racially biased. Dealing with the Mormon Church, which allowed polygamy at the time, Arthur signed the Edmunds Act in 1882 which made polygamy illegal.

Arthur also attempted to help the Native Americans in the West who had recently been placed on reservations after the Indian Wars by urging Congress to allot funds for education.

Arthur’s Declining Health

Throughout his time in office, Arthur suffered from poor health. He was diagnosed with Bright’s Disease, a kidney ailment, soon after taking office. Though he tried to keep his condition a secret, he struggled to keep up with the pace of the office and he had become thinner and looked more aged.

In an attempt to rejuvenate his health, Arthur and a group of friends took a vacation to a resort in Florida in April 1883. The trip had the opposite effect. Because the resort was easily traveled to by the press, Arthur was not able to get away from the pressures of the presidency and the stress only intensified his condition. Arthur returned to Washington more exhausted than before.

Later in August that year, at the suggestion of Senator George Vest of Missouri, the President took another vacation, this time to the new Yellowstone National Park. The beauty of this vacation was that due to the remoteness of the park, Arthur could get completely away from the press and the stresses of Washington.

He spent three weeks horseback riding, camping, and fishing in the Greater Yellowstone wilderness. This trip had the needed effect of rejuvenating Arthur’s health. The excursion also brought attention to the need for conservation in the region.

Arthur’s Last Days In Office

As the next presidential election approached, the question arose of who would be favored for the Republican nomination. Arthur at first considered seeking the nomination for his own elected term. He soon realized, however, that he lacked solid enough backing from the two main factions within the party.

There also was the question of his health. In the end, Arthur put in only a token bid, and the nomination went to James G. Blaine.

Arthur concluded his remaining months in office as a non-elected, nearly full-term President.

The 1884 election ushered in a change in power as the Republican candidate Blaine lost to Democrat Grover Cleveland.

Few people came into the office of the President under more suspicion than Chester Arthur. Though he has faded into historical obscurity as one of the less memorable U.S. Presidents, he left the office with a high degree of popularity, well respected by both political friend and foe.

Arthur’s Last Years

Arthur returned to his law practice in New York City, but his poor health prevented him from being very active with it.

Arthur became seriously ill in late 1886 and suffered a cerebral hemorrhage, dying on November 18 at the age of 57. A funeral was held for him on the 22nd at the Church of the Heavenly Rest in New York City. He was buried next to his wife in a family sarcophagus in the Albany Rural Cemetary in Menards, NY.