Table of Contents

ToggleThe Manhattan Project was a secret research project undertaken amid World War II by the United States that used some of the world’s premier scientists whose goal was to figure out a way to create an atomic bomb capable of unrivaled destructive force.

One of the most important, life-changing events of the 20th century, the Manhattan Project, brought forth the nuclear age, which still permeates today.

The Manhattan Project concluded with the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, which devastated the two Japanese cities and the people who lived there, effectively putting an end to World War II.

Origins

The Manhattan Project was borne out of the discovery of nuclear fission in 1938 by Fritz Strassmann and Otto Hahn, two German scientists.

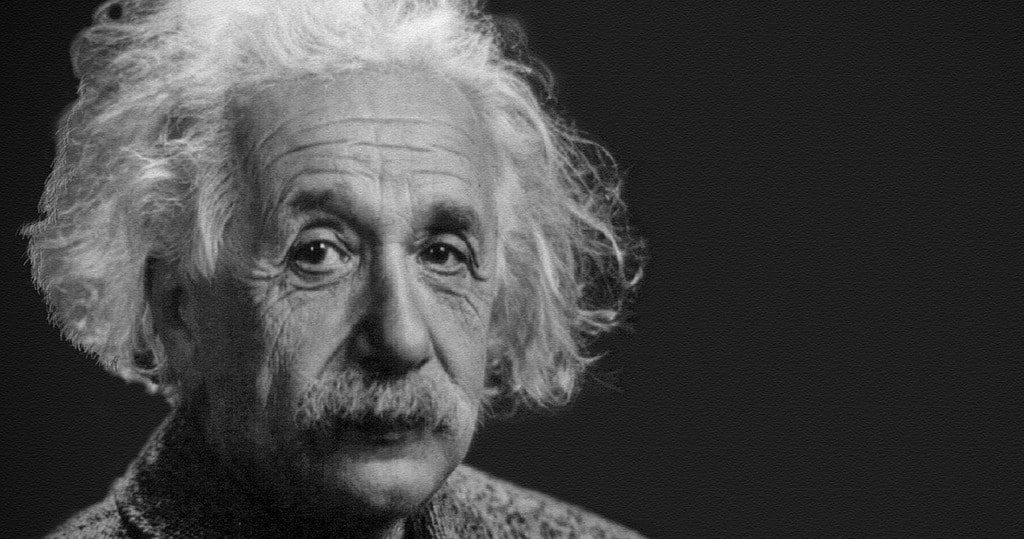

In response to this discovery, Leo Szilard and Albert Einstein wrote to United States President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, warning him that the Nazis might be attempting to build an atomic bomb to dominate Europe and the world as a whole.

Following the letter, President Roosevelt created the Uranium Committee, which combined top scientists and military leaders working together to determine the practicality of weaponizing nuclear chain reactions.

The Maud Committee

The early research dragged on slowly until early 1941 when the British equivalent to the United State’s Uranium Committee, the MAUD Committee, released a report that confirmed that developing an atomic bomb was possible and that British and United States cooperation was necessary.

University Research

Proceeding with the creation of the Manhattan Project, several universities across the United States were researching atomic energy.

Ernest Lawrence, a professor at the University of California at Berkley, oversaw the University’s “Rad Lab” there, Lawrence invented the cyclotron (also known as the “atom smasher”), which accelerated atoms capable of inducing collisions at a terrific speed of 25,000 miles per second.

At Columbia University, a group of scientists that included Herbert Anderson, Leo Szilard, Walter Zinn, and Enrico Fermi worked together and created the world’s first self-sustaining chain reaction.

Their experiment proved that nuclear energy could generate power and, in the process, demonstrated a feasible way to produce plutonium, a key ingredient in the production of an atomic bomb.

Forming of the Manhattan Project

On August 13, 1942, the Manhattan Project was officially formed. The name derived from the location of its first offices, which were located in the Manhattan borough of New York City.

General Leslie R. Groves was placed in charge of the project, which received its first significant funding from an order placed by President Roosevelt in December of 1942. The group received a whopping $500 million to get started.

Shortly after, the project’s headquarters were moved to the nation’s capital, Washington, D.C. Other project sites were scattered across the country in Los Alamos, New Mexico, Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and Hanford, Washington.

Los Alamos, New Mexico

Located in a relatively rural area of New Mexico, the Los Alamos national laboratory was the Manhattan Project’s weapons research laboratory, where most of the remaining atomic research and the actual construction of the bomb took place.

At Los Alamos, a collection of scientists and military personnel, including explosive experts, physicists, chemists, and metallurgists, worked on the secret project protected by the United States Army, which also supplied and supported the project’s efforts.

Oak Ridge, Tennessee, Hanford, Washington & Other Sites

Oak Ridge was home to several uranium enrichment plants, which were crucial in the creation of the atomic bombs. Hanford, Washington, was the home base for plutonium enrichment and where the B reactor was constructed before joining the other reactors at Los Alamos.

Other sites used in the Manhattan Project’s efforts include Cambridge, Massachusetts, and the laboratories of Harvard and MIT, Dayton, Ohio, and Canada as a collaborative effort with the Montreal Laboratory and the Chalk River Nuclear Laboratories located in Ontario.

In total, it is estimated that approximately 600,000 individuals worked on the Manhattan Project from 1942 to 1945.

Chief Scientists Involved

Robert Oppenheimer, a physicist, headed the project, and Edward Teller, another physicist initially from Hungary, was one of the project’s first and most prominent members.

Enrico Fermi mentioned earlier, an Italian physicist who fled the brutality of Mussolini’s regime, and Leo Slizard, another Hungarian physicist, was crucial in building the world’s first nuclear reactor as well as for their efforts as the project moved along.

There were many other notable scientists and researchers, including Niels Bohr, Albert Einstein, Felix Bloch, Hans Bethe, John von Neumann, Otto Frisch, and Emilio Segre, among others.

Final Preparations & Considerations

As the project progressed and neared completion, the United States Government and military began considering how and if the developments of the Manhattan Project, the atomic bombs, could or should be used.

In May 1945, new President Harry Truman and Secretary of War Harry L. Stimson established an interim committee that would be used to both make recommendations for the atomic bomb used during wartime and for the post-war organization of atomic energy.

In July of 1945, the scientific panel of the committee issued a report that recommended using the bomb against the Japanese in the seemingly interminable war.

Testing

The world’s first atomic bomb was dropped and exploded on July 16, 1945, at the Alamogordo Air Base in New Mexico.

The plutonium bomb code-named “gadget” detonated, producing an extremely bright flash of light and simultaneous heat flash, and was accompanied by a deafening roar and surge of energy in the form of a shock wave.

Get Smarter on US News, History, and the Constitution

Join the thousands of fellow patriots who rely on our 5-minute newsletter to stay informed on the key events and trends that shaped our nation's past and continue to shape its present.

The mushroom cloud produced by the bomb rose a staggering eight miles into the sky and left a bomb crater that was 1,000 feet wide and ten feet deep.

Use in Japan

Hiroshima

The United States military finally implemented the Manhattan Project’s efforts in Hiroshima, Japan, on August 6, 1945.

The bomb, code-named “little boy,” was dropped from the US B-29 bomber Enola Gay. The bomb devastated Hiroshima, flattening the city, reducing it to rubble, and killing an estimated 900,000 to 160,000 people in the four months following the bomb’s detonation.

The city of Hiroshima estimated that a total of 237,000 citizens were killed by the effects of the bomb, either directly or indirectly, including deaths from radiation, cancer, and injuries from burns.

Nagasaki

On August 9, three days after Hiroshima, the United States dropped a second atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Nagasaki. The bomb, nicknamed “fat man,” killed an estimated 80,000 people and destroyed the city.

The Japanese surrendered to the United States on August 14, 1945, effectively ending the Second World War.