Table of Contents

ToggleIsolationism

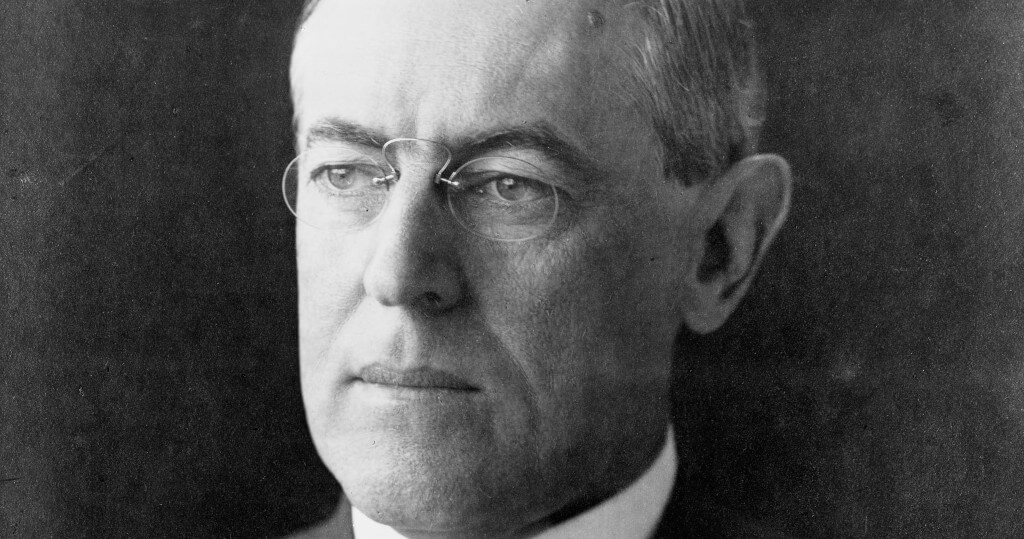

The Great War, or the First World War, raged for nearly three years before German aggression drew the United States into the conflict. The public yearned for peace and the country, led by President Woodrow Wilson, to remain isolated.

The distant nature of the conflict and lack of public support made it easy for the United States to stay aloof.

That was until German aggression in the form of unrestricted submarine warfare against allied ships sailing through the North Atlantic and Mediterranean seas, coupled with an appeal to Mexico in the form of the Zimmermann Telegram, turned the tide against them.

German Tactics in WW1

On the ground

The German military and their allies, the Central Powers, comprised of Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria, had devastated and essentially defeated the Russian military early on in the conflict.

Russia had devolved into a civil war by 1917. On the Western front, a bloody quagmire slogged on as the conflict turned into a notoriously brutal stalemate punctuated by trench warfare.

German naval tactics

Great Britain swiftly blocked the North Sea and the English Channel after the opening of hostilities in 1914.

The German military leadership retaliated against the blockade by using its advanced submarine fleet (U-boats) to destroy enemy combatants and neutral ships being used to supply and reinforce the British. The Germans attempted to starve the British before the blockade led to their defeat.

The sinking of the Lusitania

In May 1915, a German U-boat, U-20, torpedoed and sank a passenger ship, the Lusitania, off the coast of Ireland. The death toll was staggering.

Approximately 1,200 passengers were killed, including 128 Americans. The sinking of the Lusitania caused an uproar amongst the American populace and leadership.

Attacks resume

Following the Lusitania’s sinking, which both the allies and Americans considered an act of indiscriminate warfare, the United States government was very close to entering the war.

Germany backed down from the conflict at this time and halted unrestricted submarine warfare, especially attacks against passenger ships.

In 1917, the German High Command ordered the resumption of open submarine warfare against any targets in the Atlantic Ocean, including passenger ships.

Wilson takes action (sort of)

President Woodrow Wilson finally took action when he broke diplomatic relations with the Germans in February 1917, shortly after they resumed unrestricted submarine warfare.

Still uncertain about public support, Wilson avoided asking Congress to declare war, arguing that Germany had yet to commit any “actual overt acts.”

German submarine warfare resumed in March of 1917, with the sinking of numerous ships and the death of American sailors and citizens.

Zimmermann Telegram: The Final Push

Despite the relentless and devastating German submarine warfare, American public opinion remained largely apathetic regarding entering World War I.

However, large portions of the press, members of Wilson’s Cabinet, and other public leaders were hawkish and demanded an entrance into the war.

The Zimmermann telegram, an intercepted correspondence between Germany and Mexico, was a crucial turning point and galvanized the public into supporting America’s entry into the war.

Arthur Zimmermann

Arthur Zimmermann became the German Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs following the previous secretary, Gottlieb von Jagow’s resignation in November of 1916.

Jagow left his post following the German High Command’s plan to resume unrestricted submarine warfare.

Zimmermann was chosen to replace Jagow as he was considered a sycophant, amenable to the questionable German practice of unrestricted submarine warfare.

Initial message

On January 16th, 1917, Zimmermann sent a secretive message to the then-German Minister in Mexico, Heinrich von Eckardt, instructing Eckardt to meet with his contacts in the Mexican government to propose a military alliance should the United States decide to enter the war against Germany.

Zimmermann sent this message on the presumption that Wilson and the United States would soon declare war on Germany after their U-boats’ renewed attacks.

The Germans hoped that by enlisting Mexican help, they could slow down shipments of supplies, ammunition, and even troops and force the Americans to fight on two fronts akin to the German situation in Europe.

The offer

Zimmermann’s telegram to Heinrich von Eckardt in the German Embassy included an offer to the Mexican government should they help Germany win the war and defeat the United States in the process.

In the case of Mexican support and joint victory, the Germans promised to provide “generous financial support” and the reclamation of lost territory in the United States, dating back to the Mexican-American war.

The offer concluded “that Mexico is to reconquer her lost territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona.”

Discovery

Due to Great Britain severing Imperial Germany’s direct, underseas communication links with North America near the beginning of the war, sensitive German messages to North America had to pass through neutral countries in transit.

Zimmermann’s telegram passed through the American Embassy in Berlin before arriving in London, and the American Embassy in Washington, D.C., before finally arriving in Eckhardt’s hands on January 19th.

Zimmermann remained unaware that his supposedly secret message had been intercepted and decoded in transit by the British Naval Intelligence, who then passed on the contents to President Wilson.

Wilson’s reaction

According to reports, Wilson received the news from London when they were able to decode the telegram in late February.

This news did not immediately affect the president’s decision to enter the war against Germany, but it did cause him to lose all faith in the German government.

Publication

On March 1st, 1917, the press broke the news of the Zimmermann telegram splashing the details of Germany’s treachery on the front page of newspapers across the country.

Get Smarter on US News, History, and the Constitution

Join the thousands of fellow patriots who rely on our 5-minute newsletter to stay informed on the key events and trends that shaped our nation's past and continue to shape its present.

A few days after learning of the telegram’s contents, Wilson informed the state department to make the information public, leaking the sordid news to the press.

The press’s coverage of the secret telegram led to widespread outcry from a now seething American public and, for the first time, strong demands to enter the war against Germany and the Central Powers.

Declaring War

Spurred on by Zimmermann’s telegram and the sinking of three United States Merchant ships on March 18th, resulting in a large loss of life, President Wilson decided to enter the war on March 20th.

At a special session with Congress on April 2nd, Wilson delivered a stirring message for going to war in front of the congressional body.

The Senate approved the resolution for war on April 4th and the House on April 6th. Wilson signed a resolution that same day, and the United States was officially at war with Imperial Germany.