Table of Contents

ToggleThe filibuster is a procedural strategy used in the United States Senate to preclude a measure from coming to a vote.

A filibuster can be used to block legislation, nominations, and other matters.

Senators may filibuster by speaking on the floor of the Senate for an extended period of time. A filibuster can also be caused by a senator “holding the floor” and refusing to return it to the Senate.

The filibuster is not specifically mentioned in the rules of the Senate but has been used since its early days.

The term “filibuster” comes from a Spanish word meaning “pirate.”

Filibuster Origins

In the early days of the Senate, senators would use filibusters to prevent votes on bills they did not like. Today, the filibuster is used less often than in the past, but it remains an important part of the Senate’s procedures.

To end a filibuster, the Senate can vote to “invoke cloture.”

Cloture is a procedural vote that requires 60 votes to pass. If the cloture rule is invoked, the Senate must vote on the bill or nomination within 30 hours.

A Short History of the Filibuster

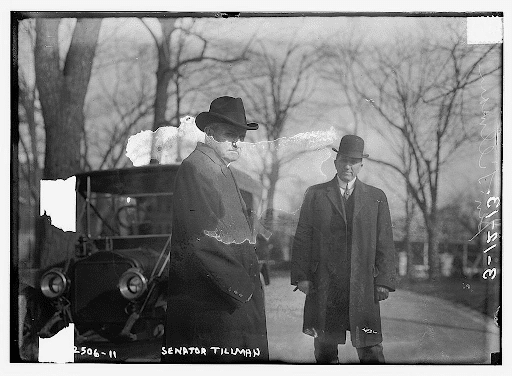

As the swashbuckling origins of the word suggest, the filibuster has been a feature of Senate procedure for hundreds of years. One of the earliest recorded usages of the legislative filibuster in the Senate was in 1841.

In that year, Senator John C. Calhoun of South Carolina – notable for his opposition to majority rule and support of slavery – blocked a bill that would have authorized establishing a new national bank using a filibuster.

Calhoun’s filibuster lasted for 24 hours and set a precedent for future use of the tactic.

Over the next few decades, senators occasionally used filibusters to block votes on bills they opposed. However, it was not until 1917 that the filibuster began to see more frequent usage.

That year, the Senate adopted a filibuster rule that allowed a two-thirds vote of the Senate to end a filibuster.

In 1925, filibuster reform was introduced as the Senate lowered the required vote to three-fifths of the United States Senate (60 votes).

In 2010, the cloture threshold was lowered further to a simple majority – though only for nominations.

Notable Filibusters

Not all filibusters are created equal, and some are worthy of special consideration.

The tactic fundamentally depends on an individual senator’s ability to stand and talk continuously for heroic stretches of time.

Filibusters are often impressive feats of endurance and talking at extreme length about anything that can be linked to the debate at hand, however tenuously.

United States Senator Strom Thurmond, 1957

The record for the longest single filibuster to date belongs to Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, who in 1957 spoke on the Senate floor against the Civil Rights Act for a total of 24 hours and 18 minutes.

Get Smarter on US News, History, and the Constitution

Join the thousands of fellow patriots who rely on our 5-minute newsletter to stay informed on the key events and trends that shaped our nation's past and continue to shape its present.

Thurmond prolonged his filibuster largely by reciting historical documents, ranging from the Declaration of Independence to George Washington’s farewell speech.

Many other senators followed his example, continuously filibustering the Civil Rights Act for 57 days.

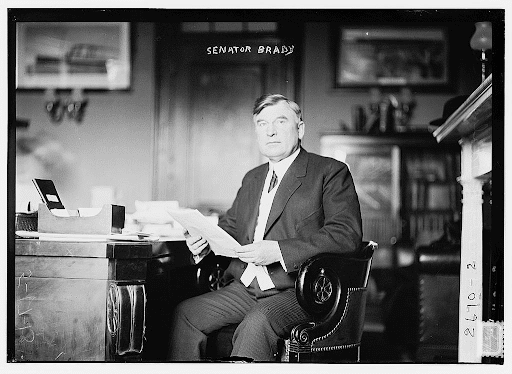

United States Senator Robert La Follette Sr., 1908

In what many might consider a substantially less ignoble cause, Senator Robert La Follette Sr. of Wisconsin took to the Senate floor to filibuster the Aldrich-Vreeland currency bill for 18 hours and 23 minutes.

The bill would have permitted the United States Treasury to lend money directly to banks during times of financial crisis.

This may seem quaint in light of the century since. However, La Follette saw the bill as a threat to the working poor, who stood to benefit very little from a measure they would end up paying for.

The Legitimacy of the Filibuster

Whether or not the Senate filibuster rule is a legitimate means of influencing the legislative process is an open question with compelling arguments both for and against.

Essentially, the filibuster amplifies the legislative impact of the Senate minority, providing it with a soft veto on any legislation that passes through the chamber.

On its face, this is anti-democratic, as it frustrates the will of the Senate majority party as chosen by the electorate. There are, however, several problems with and counterarguments to this perspective.

Arguments for the filibuster

Supporters of the filibuster insist it is a vital tool in protecting political minorities from the excesses of a majoritarian rule which may seek to deprive them of their rights and degrade their well-being.

For example, we may imagine a scenario where a minority ethnic group is represented largely or entirely by a single political party.

The opposing party may seek to take punitive action against this ethnic group, either out of racial animus or as an easy way of appeasing their base.

Should the opposing party gain majority support, the ethnic group’s only recourse for political protection is the counter-majoritarian (or anti-democratic) legislative institutions.

Arguments against the filibuster

There are, however, counterarguments to this standpoint in turn. The foremost is that the very scenario above is so unlikely that it does not merit serious consideration.

If complicated thought experiments involving very specific scenarios are required to justify the filibuster, is it not simply more likely that the filibuster itself is unjust?

Secondly, even if we accept the value of counter-majoritarian institutions, it can be argued that the construction of the Senate itself is already sufficiently undemocratic.

Every state has exactly two senators, so residents of sparsely populated states are represented much more strongly than those with greater populations.

The consequences

The practical consequence is that the party representing more rural regions has a structural advantage in the Senate, which in the current era is the GOP (Grand Old Party).

Though this is only a product of current political alignments, there is no inherent reason one party should be favored in the city and the other in the country.

Here To Stay

Depending on your perspective, the filibuster is a bulwark against the ravages of mob rule or a morally offensive and anti-democratic relic of an age where landowning aristocrats ignored the people’s will.

For or against, it is a centuries-old feature of our legislative process and is unlikely to go away any time soon.