Table of Contents

ToggleThe Commerce Clause grants the United States Congress power to “regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes” (Article 1, Section 8, Clause 3 of the United States Constitution).

Those three types of commerce are often separated into three individual clauses: the Foreign Commerce Clause, the Interstate Commerce Clause, and the Indian Commerce Clause.

- Foreign Commerce refers to any commercial matters between the United States and a foreign nation. Therefore, the Foreign Commerce Clause comes into play when the United States government intervenes in trade between the United States and another nation.

- Interstate Commerce refers to any commercial matters between different states. Therefore, the Interstate Commerce Clause is used when Congress exercises its power over the states, regulating commerce between them as it sees fit.

- Indian Commerce refers to any commercial matters taking place within Native American tribes. Therefore, the Indian Commerce Clause is invoked when the government intervenes in these matters.

The Tenth Amendment of the United States Constitution grants each state the right to self-government, so state and federal governments typically regulate commerce.

Congress may get involved in matters of commerce if it has reason to believe that trade is being improperly regulated or interstate economic activity needs more intensive management. It does not exercise legislative power over individual states or peoples lightly, so if the Commerce Clause is invoked, it is with significant reason.

Why Was the Commerce Clause Created?

Prior to the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776, the United States was divided into thirteen colonies, each governed by an independent legislative body.

In 1789, the Constitution of the United States of America united those thirteen colonies as one nation, establishing a body of governing law that gave all the states fundamental legislation to follow.

And though each of the American states is subject to its current laws and regulations, the United States Congress acts as an overarching body of power that can make and amend laws due to the authority granted by the 1789 Constitution.

The Commerce Clause is just one part of American constitutional legislation that allows Congress to participate positively in state laws and government.

Though all fifty states have their own governments that make their own laws and policies, Congress exists to offer foundational regulation of these laws and policies, with the aim of protecting the United States’ peoples and trades.

It has the power to act as and when it chooses, based on economic developments, deals, and exchanges within the United States and outside of it.

Interstate trade has historically been slowed down by barriers imposed individually by different states to safeguard their own peoples and businesses against competitors.

Get Smarter on US News, History, and the Constitution

Join the thousands of fellow patriots who rely on our 5-minute newsletter to stay informed on the key events and trends that shaped our nation's past and continue to shape its present.

Independent state governments have the power to establish internal legislature, but this can make interstate trading more difficult if policies clash or seek to put one state at an advantage over the other.

The Commerce Clause grants congressional power to override independent legislatures, making it easier for states to enter into trade deals with each other and for the United States to establish trade with foreign nations.

Prior to the introduction of the Commerce Clause into the United States Constitution, Congress could not establish trade deals with other countries because each state had complete control over its own commerce. This threatened the longevity of American goods in the global market, isolating the United States and preventing it from creating beneficial economic relationships.

What Constitutes ‘Commerce’?

In the context of the Commerce Clause, ‘commerce’ refers to trading, selling, conveying, and exchanging goods intrastate, interstate, or internationally.

Commerce’ can also refer to people, which is why the Commerce Clause allowed the United States Congress to abolish the slave trade with other nations in 1808 (the earliest date permitted) and other international commerce powers.

Commercial goods are often physical, mass-produced commodities that can be transported and exchanged as part of internal or external trade deals. This tends to exclude goods that are produced via other methods, such as agriculture or manufacturing.

Though these goods are not typically categorized as ‘commerce,’ they can also be traded, so sometimes the lines between what constitutes ‘commerce’ and what does not are blurred. When this happens, there are opportunities for defendants indicted under the Commerce Clause to challenge Congress.

Sometimes, the meaning of the word ‘regulation’ is also called into question in cases where the government exercises its power to use the Commerce Clause. In this context, ‘to regulate’ means to prescribe and impose authority, so when Congress regulates commerce, its power can be presumed to be absolute.

However, some people object to this on the basis that absolute power over commerce gives Congress the constitutional right to go as far as prohibiting or ending some forms of commerce completely.

Criticism of the Commerce Clause

The Commerce Clause is so significant because the United States Congress is a powerful legislative body that only intervenes in federal governmental matters if it has substantial reason to believe that commerce is being incorrectly regulated by those involved.

Though it gives authoritative power to Congress, the Commerce Clause was designed with the wider United States peoples in mind.

Congress enacts its authority to protect the economic state of the country. Still, it also intervenes to ensure that American citizens are financially secure and can benefit from strong trade Commerce.

The Commerce Clause has been criticized for giving Congress to much authority to intervene in interstate and international economic matters because it overrules the independent authority that state governments have.

Dormant Commerce Clause

This criticism has been developed into a legal doctrine called the Dormant Commerce Clause, which refers to the implicit prohibition of state legislation that discriminates against or burdens interstate or international commerce.

As a result, states effectively lose their federal authority over Commerce when Congress invokes its constitutional right to intervene.

Criticism of the perceived power imbalance between the United States Congress and individual state governments is long-enduring.

A lot of people believe that economic and trade matters should be wholly in the control of the states themselves, regardless of the barriers that exist between states and foreign nations when it comes to entering into trade agreements and exchanging goods.

The existence of the Dormant Commerce Clause demonstrates that individual states are still pushing for increased economic independence from Congress.

Support for the Commerce Clause

Despite the criticism, there is also support for the Commerce Clause. It is an example of the exclusive regulatory powers that the United States Congress possesses, helping to bolster internal and international trade deals and get the best outcome possible for American citizens, goods, and businesses as their participation in huge markets.

When the Commerce Clause is invoked during international trade deals, Americans can rest assured that they are being protected and fairly represented.

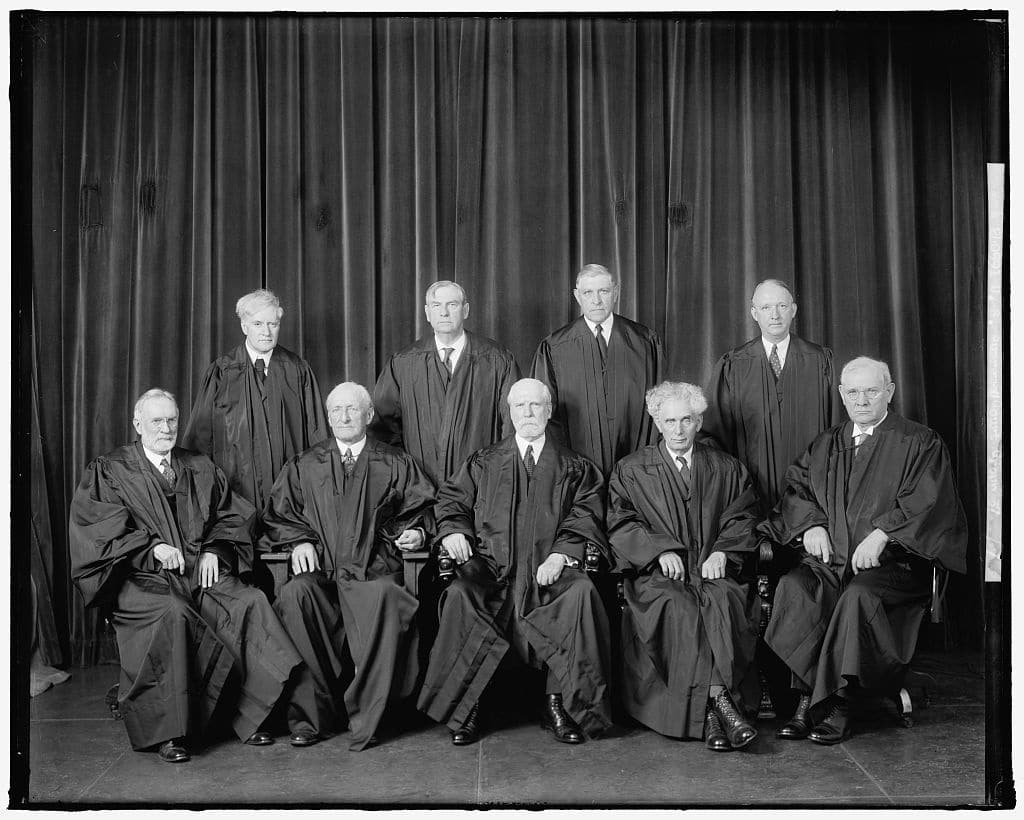

The Supreme Court has found in favor of Congress multiple times when its right to use the Commerce Clause has been called into question.

Congress has been legally determined to invoke the clause when it feels that the United States economy is at risk of damage, decline, or being taken advantage of.

Its primary objective is to protect the economy wherever it can, so there is much power in the Commerce Clause and support for Congress when it has been unfairly challenged.

The Commerce Clause is also not designed to intervene permanently in federal government matters. Each state is entitled to and, succeeding enactment of the clause, retains its right to self-govern, so Congress cannot extend its powers beyond specific intervention into trade matters.

It is also possible for American citizens to challenge the Commerce Clause, such as in the case of United States v. Lopez (1995), so, despite being a fundamental body of power, Congress is not exempt from probing when necessary.

The Commerce Clause in Action

The Commerce Clause has been invoked by the United States Congress several times since it was first signed into constitutional law back in the eighteenth century.

One example occurred in 1903, the case of Champion v. Ames. Charles Champion was arrested for shipping lottery tickets from Texas to California. The 1895 Federal Lottery Act established the prohibition of interstate lottery ticket sales, so Congress was able to indict Champion via the Commerce Clause for breaking that Act.

Champion challenged this move by Congress on the grounds that ‘regulating commerce’ is not synonymous with ‘prohibiting commerce’.

However, Congress’s use of the Interstate Commerce Clause was successful, with support backing its move 5-4. Those who voted in Champion’s favor posited that prohibiting commerce entirely through the Commerce Clause was an overstep by Congress.

However, the Supreme Court recognized that Congress’ power to intervene in interstate trading matters is plenary.

On the other hand, there have also been instances where the Commerce Clause has been invoked only for the responding dissent to be successful.

Gun-Free School Zones Act

In 1990, Congress established the Gun-Free School Zones Act, which resulted in a teenager named Alfonso Lopez being arrested for having a gun on his person while at school in San Antonio, Texas, two years later.

He was charged with violating the Gun-Free School Zones Act. His attorneys argued that it had overstepped the boundaries of the Commerce Clause. Lopez was still sentenced to six months imprisonment.

In 1994, the case was brought before the Supreme Court after Lopez appealed his conviction. It was argued on his behalf that the government should not have invoked the Commerce Clause because the Gun-Free School Zones Act was not a matter of regulating interstate commerce, completing trade deals, or intervening in economic matters in any way.

In response, Congress argued that gun possession posed an economic threat should it lead to the outbreak of violent crime. Despite this counterargument, the Supreme Court found in Lopez’s favor and emphasized the lack of correlation between commerce and gun possession.

The Future of the Commerce Clause

Despite being found to have improperly enacted the Commerce Clause in the past, as in the case of Alfonso Lopez, Congress has retained its power to invoke the Foreign Commerce Clause, the Interstate Commerce Clause, and the Indian Commerce Clause whenever they think constitutional intervention is necessary to protect the American economy.

All three give Congress plenary authority over the states, foreign relations, and the independent Indian tribes.

The future of the Commerce Clause will likely continue to be used much the same as in the past. Although, with states pushing harder than ever for a stronger focus on self-government, there might be more challenges prompted by enactment of the Commerce Clause.

If individual states feel that the United States Congress is interfering in their internal economic matters, the opposition is only to be expected.

The United States economy is boosted massively by interstate and international trade, so it also stands to reason that Congress will be more eager than ever to invoke the Commerce Clause if it deduces that problems might threaten the country’s economic status.

Billions per year are generated by exports of items such as petroleum, gold, and aircraft parts, so the United States stands to gain a lot from continuing to develop its successful trading relationships.

As all legislative power is vested in Congress, it is the most authoritative body in the United States. Congress can make laws, change existing laws and intervene in stately matters as a dominant power, all of which allow it to exercise full control over the American economy, its trade deals, and the people involved in commerce.

The Commerce Clause is incredibly important when regulating such matters, so it is highly unlikely that Congress will invoke it less as the years go on.